Hello!

Spring is finally in the air here in Stockholm, and the city’s energy is shifting. Everything feels lighter, brighter, more hopeful. Which is exactly how I felt after meeting this week’s Q&A guest, Hanna Thomas Uose.

Hanna is a true multidisciplinarian. Formerly Chief Product Officer at 350.org (where her team built the tech that helped mobilise 7.6m people for the 2019 Global Climate Strikes), Hanna has co-founded gender justice community Level Up, the street harassment mapping platform iStreetWatch, and organisational consulting firm Align, where she currently works. On top of being a serial founder, Hanna’s also a facilitator, researcher, coach, and fiction writer. She’s currently completing an MA in Prose Fiction and won the Morley Prize for Unpublished Writers of Colour late last year.

Unsurprisingly, I had a broad range of questions for Hanna. We touched on everything from the relationship between Agile and feminism to the impact of internalised capitalism on the workplace.

Take your time with this Q&A. Hanna’s rich and multi-layered answers will give you more with each reading.

You’ve previously said that Agile is inherently feminist. Can you unpack this for us?

Absolutely. I wrote an article in 2019, titled Why Don’t We Just Call Agile What It Is: Feminist. The headline was intentionally eye-catching, but the thrust of what I was trying to say is that Lean Agile principles embody many of the same values that underpin progressive, punk, queer, anti-establishment movements: a focus on collaboration over hierarchy, experiments, playfulness, and strong relationships.

At the time, I was Chief Product Officer at 350.org, building a team from the ground up and trying to solve a fair amount of technical debt. I’d come from SumOfUs.org, a digital-first organisation that was pretty agile in its way of working. In my new role, I met some resistance from those who didn’t have that background. One concern I heard was, why should we care about Agile, or Lean, or testing MVPs, when these are all concepts seemingly developed and sold by white guys in Silicon Valley in order to benefit big business?

I understood that resistance, but my feeling was that nothing in the Agile Manifesto was new – it was a repackaging of concepts that are second nature to progressive, feminist, queer, and anti-racist organisers, such as the need to be open to change, service-oriented, and willing to fail. If you compare the Agile Manifesto to the Riot Grrrl Manifesto, for example, there is a delicious amount of crossover. The fourth Agile tenet of “responding to change over following a plan” is an echo of the Earthseed tenet in Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower: “All that you touch You Change. All that you Change, Changes you. The only lasting truth is Change. God is Change.”

The Agile Manifesto was put together in 2001, the Riot Grrrl Manifesto was developed in 1991, and Octavia Butler published her novel in 1993. I’m not suggesting that the 17 authors (all men) of the Agile Manifesto were directly inspired by feminist or radical theory, but I did want to credit those thinkers who were already operating by the same principles and provide a pathway towards reclaiming this way of working for those in the progressive, non-profit space.

The first time we spoke, you said that both startups and non-profits can be intense workplaces. Why do you think this is the case, and how can tech and non-profit employees thrive in such an environment?

It feels important to say that lots of jobs are intense outside of startups and non-profits. Every job has its constraints, and there are many more sectors that are harder on the body, mind, and daily schedule than either of those we’re grappling with here.

I do think, though, that what startups and non-profits have in common is a landscape that is constantly and dramatically shifting. Whatever you do, the conditions you’re operating in will be quite different 12 months out, whether that’s because of funds, politics, or technological advancement. This context makes it particularly hard to plan, and if your team does not have the trust, alignment, strong relationships, right infrastructure, or clarity of vision, as well as the ability to be flexible, they will suffer.

Is it possible for tech and non-profit employees to thrive in this environment? I think thrive might be too strong a word when, at least in the UK, people are currently struggling to pay their bills during the cost of living crisis. First, our foundational needs must be met: proper wages and the ability to rest and care for our bodies and lives outside of work. I’m glad to see the 4-day work week taking root in the non-profit sector, but we need more funders who understand what it takes to sustain movement building – namely, people who are not in crisis.

On an individual level, part of it might be redefining our relationship to work and untying the knots of internalised capitalism. Although, tech companies and non-profits can be particularly savvy in trying to get around that, replacing the language of work with that of family. For example, the tagline for Salesforce’s internal culture work is ohana, the Hawaiian word for family. But work is not your family. That doesn’t mean love and care can’t show up in the workplace – it can and should. But I fear that the language of family is often brought in when an organisation, perhaps subconsciously, sees it as an effective route to exploiting their workers.

As someone well-versed in the idea of internalised capitalism, what’s your stance on resilience? Is it a positive capability or just another way for neoliberalism to deflect responsibility?

I think there are so many ways to answer this. I totally understand the reluctance to trumpet resilience as a favorable trait within the workplace, as it’s a concept easy to manipulate in that context and can be used as a stick to beat people with if they do not display the requisite amount of resilience in the face of poor working conditions.

I just googled the etymology of resilience. It comes from the Latin verb resilire, meaning to rebound or recoil – like elastic. But, when stretched to a certain point, elastic snaps and can’t recover its original shape. This might be the inherent problem with the concept of resilience, this assumption that we can always bounce back. I’ve noticed the word “antifragile” gaining traction instead of resilience – to signal that it is possible to “build back better,” as it were, or experience some version of post-traumatic growth. While that is sometimes true, it seems to me that the pushback to resilience being used as workplace rhetoric is rooted in the acknowledgment that it’s not always possible to recover our original ‘shape’. Our ability to recover depends on the immediate situation but also our individual histories, the effects of generational trauma, and ongoing oppression in the external environment.

This aspiration towards recovering our original shape also denies any possibility or desire for change, perhaps. Do we want to always recover to the same shape, or do we want to acknowledge that adversity has changed us and adopt another shape in response – both individually and collectively? If organisations were more open to being changed, there might not be such a pressure to be individually resilient.

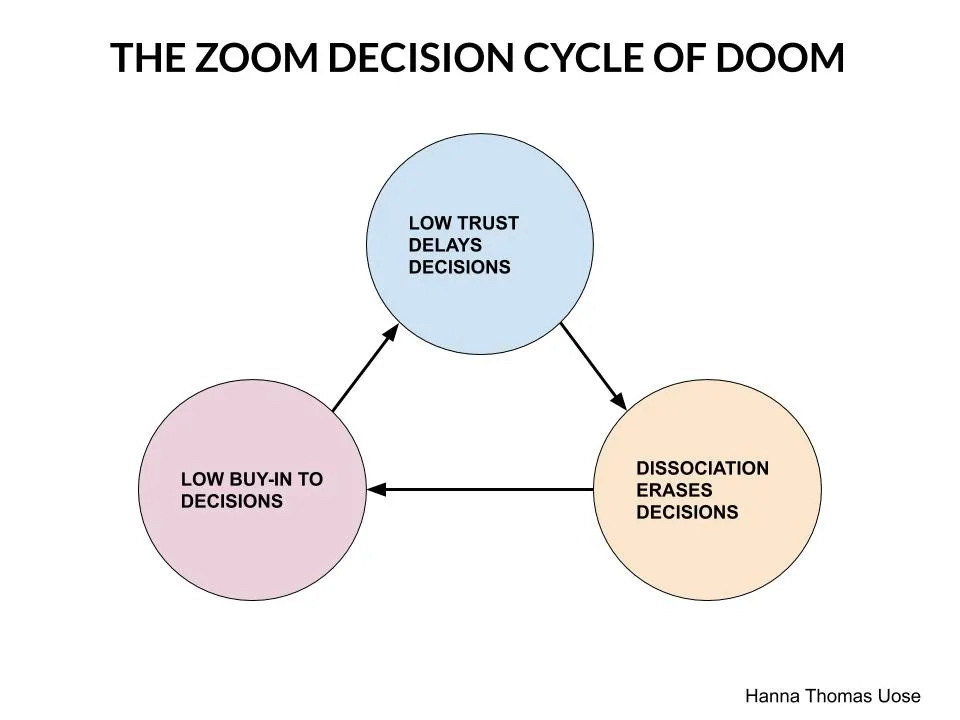

Having said that, I’m not sure we can abstract the concept of resilience so much that we dismiss the idea entirely as neoliberal. We do need a certain amount of resilience to meet the day, to deal with the human condition, to listen to loved ones, and sit with discomfort. We need to trust and hope that difficult experiences may lead to new, joyful ones. I think the difference might lie in our level of agency – we don’t get to choose, in daily life, what we have to face. Grief finds us. But, at work? We should have some agency to choose what is a struggle and what is not. For example, being asked to be resilient in the face of eight hours of Zoom meetings a day, or being overworked while underpaid, without a pathway to change, doesn’t feel like a legitimate request.

At the same time, when acting collectively, staff do have the power to shape the culture of their organisation, and can choose how to wield that power. Maurice Mitchell’s recent article on Building Resilient Organizations contains many helpful provocations along these lines.

Your skills and experience are so wide-ranging. If you had to pick one discipline to dedicate the next 10 years to, what would you choose and why?

Working across social change, technology, and the arts, my approach is inherently multidisciplinary (or antidisciplinary), so it feels impossible to pick one sector or discipline to dedicate myself to. Ill-advised, maybe, too, since I think the work of joining the dots and building bridges between disciplines is crucial in the face of the scale and complexity of the challenges we face. But, I can narrow my work down to one question: ‘What if?’

What if things were different? What if we organised things in this other way? What if we added this element or subtracted it? ‘What if’ is at the heart of my work, activism, and creative practice. As Walidah Imarisha said, “Any time we try to envision a different world – without poverty, prisons, capitalism, war – we are engaging in science fiction.”

Over the next decade, I’m looking forward to combining the practical skills I’ve gained over fifteen years in the non-profit sector with more creative and imaginative work – to explore this ‘what if’. I feel lucky to have done this with MAIA, helping them to design an organisational structure that uses metaphor as its organising principle.

At the moment, Hoda Baraka, my co-founder at Align, and I are working with Lauren Parater and Shanice Da Costa at UN Global Pulse to research how art and creative practice can serve organisational transformation. I’m feeling really energised by it and the acknowledgement that a huge, imaginative leap that goes beyond traditional, ‘left-brain’ ways of thinking is required in order to achieve wholesale change for people and planet. Of course, big tech companies have long championed the power of creativity and hired people like Ivy Ross to lead their design work. It’s time that the progressive, non-profit space valued creative practice in the same way. I’ve enjoyed reading about the Artist Placement Group lately, and the role of art in policy-making.

I’m also looking forward to spending this summer with Migrants in Culture, helping to deliver a pilot programme aimed at building the creative capacity of migrant organisers. I’ll be leading speculative writing workshops, creating space to imagine and describe the life-affirming cultures, institutions, and infrastructures that will replace carceral systems. Collective imagination work could be dismissed as indulgent, but to me, it seems like an absolutely crucial and unavoidable part of the journey towards another world. There’ll be more information about the programme to come on Migrant in Culture’s channels this spring.

Is it fair to say that your experiences as a founder all involve taking a digital-first approach to solving complex societal challenges? Could you share one of your top learnings from working this way as a founder?

Level Up, a community working for gender justice in the UK, definitely took a digital-first approach at the beginning. The group of co-founders all had a background in digital campaigning, and we were influenced by Ultraviolet in the States and a similar, digital-first feminist organisation in Australia. We started talking about it in 2014/15, when the context was very different, and digital-first organisations could grow rapidly and organically without paying for ads. The landscape has changed, and it’s not so easy to focus just on online organising. Janey Starling and Seyi Falodun-Liburd do an excellent job of leading Level Up now, taking an approach that combines a variety of offline and online tactics.

Whether an organisation is digital-first or not, some top learnings for me have been:

The importance of testing and taking an iterative approach. You need to know that the offer is landing and adding value to what is already out there.

Aim for ‘digital-informed’ rather than ‘digital-first’. Make sure that what you’re communicating will resonate with your audience, but balance that with the vision/mission/principles of your organisation – or chaos will reign.

Coalition-building is key. No one organisation can hold the complexity of tactics required to meet the complexity of the system. The mass mobilisation approach of digital-first organisations has a role within a larger movement that embraces a diversity of tactics (whether that’s lobbying, organising, advocacy, etc). Coordinating all that requires building strong relationships at the coalition level, an area I’d love to get more involved in.

You describe yourself as someone who’s building new worlds, in practice and in prose. What are the new worlds you’re trying to build in practice? And how does the time you spend writing prose fiction affect the way you show up in your role as a coach and strategist?

The worlds I’m trying to build in practice are ones where relationships are strong; with ourselves, each other, our fellow creatures, and the earth. Where all people have full bodily autonomy and can expect to be treated with dignity and respect. This vision of the world draws on the leadership of indigenous thinkers like Robin Wall Kimmerer and black, queer feminists like bell hooks. I refer to worlds, as opposed to a singular world, in order to acknowledge that any collective vision will include multiple worlds and multiple centres.

In terms of how my coaching practice and strategy work is influenced by writing fiction: for me, writing is about creating the space for a reader to have a particular, guided experience, noticing how they’re relating to the content along the way, so as to draw their own conclusions. The author can be as instructive as they want, but ultimately what the reader takes away is entirely dependent on them. Reading is inherently collaborative and creative in that way. I did an online workshop with Sheila Heti during lockdown, where she encouraged us to share a sample of our work in small groups, and then return each other’s work with all of the thoughts we had while reading, written between the lines. You could see that each person’s experience of the same piece radically differed based on their memories, references, and contexts. It’s the same with coaching. You hold a space for your coach partner to ask and answer their own questions while being there as a guide along the way.

As a strategist, a visioning process is key to defining an organisation’s objectives. There’s a big overlap there with speculative thinking, collective imagination, and fiction – we’re back to that ‘what if’ question again. When it comes to writing strategy, I move into more of a linear, problem-solving mode. It’s this combination of ways of thinking that I most enjoy – that journey from the north star to the map.

How can the tech and non-profit sectors come closer together?

There’s a lot that these sectors can learn from each other. For non-profits, it is vital that they invest in digital skills and infrastructure. Digital transformation processes are not sexy by any stretch of the imagination, but they are crucial if an organisation is to achieve its mission. I’ve been working with Greenpeace International over the last three years on their digital transformation, and it is great to see an organisation of their size and heft invest at a significant scale. Of course, the ability of non-profits to do this is dependent on funders understanding how much technology costs – both infrastructure and staffing.

In terms of the tech sector, I’ll come back to the agile / feminist article. The day it was published, someone posted the link onto a Silicon Valley messageboard, thinking it might provoke some interesting dialogue. Instead, a lot of tech bros with time on their hands organised to report it to Medium at the same time, and it was taken down. Ron Jeffries, one of the original authors of the Agile Manifesto, saw this happen on Twitter and stepped in to get the article reinstated. It was all very dramatic, considering that the article itself is so innocuous. There is a certain fragility, a fright within some pockets of the tech sector that, at best, want to see themselves as above or apart from politics and, at worst, are working very hard to support dangerous demagogues. I’m not sure what we do about it, but I’m ready to work with anyone who has suggestions.

What three books or other media have impacted you most as a leader and why?

Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown

A beautifully creative, interdisciplinary book, pulling on the wisdom all around us.

Jim Henson: The Biography by Brian Jay Jones

Jim Henson does not often come up in conversations I’m in about innovation, but he (along with the other creators of Sesame Street) raised a generation of children around the world, with principles of fairness, justice, play, silliness, and sincerity. This book is a very thorough record of his work ethic and dedication to experiments.

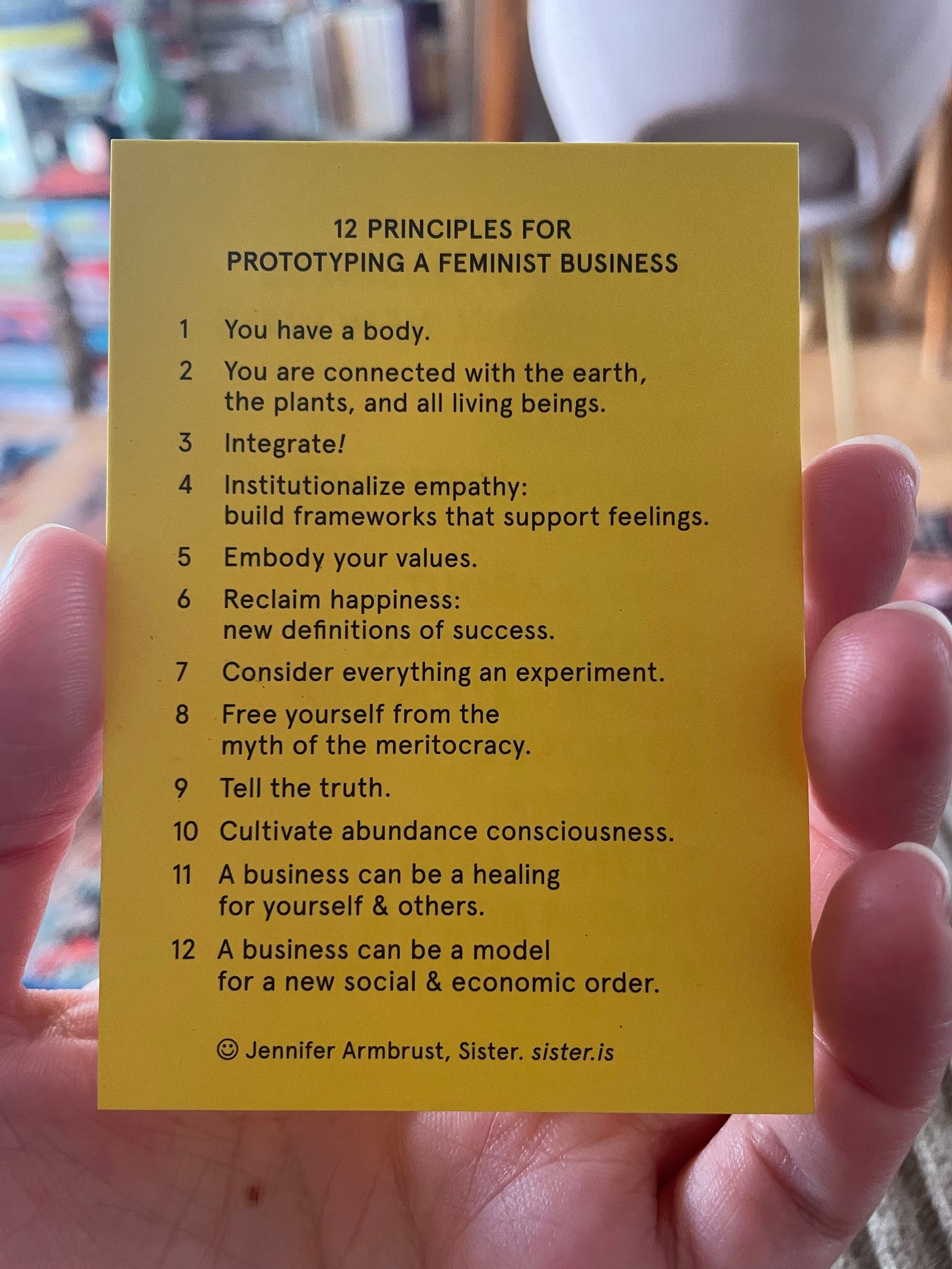

Proposals for the Feminine Economy by Jennifer Armbrust

The artist Jennifer Armbrust’s 12 Principles for Prototyping a Feminist Business were key to the development of Align, which I co-founded with Hoda Baraka in 2020.

More questions for Hanna? Email hanna@wealign.net. Or find her on Twitter and Instagram.

Thanks so much for reading!

Lauren

What a fantastic read! So rich and layered. Exactly as promised, this is a read-once-then-come-back-again-and-again treasure. Thank you Lauren and Hanna. 😊

Just read this brilliant interview and about to start it again with pen and paper in hand! I’ll be sharing this widely.