#78: The second curve

Learning to embrace renewal and change

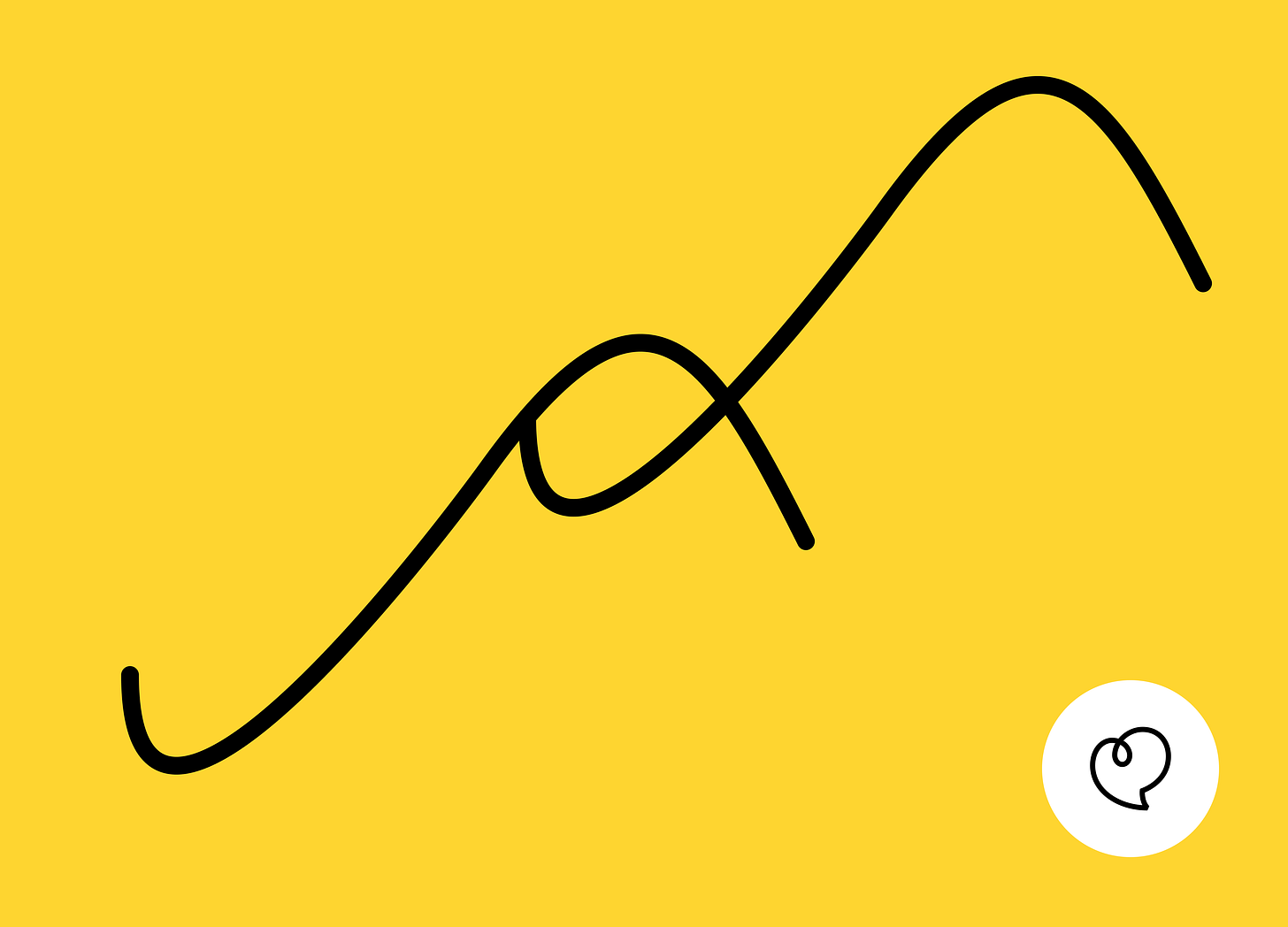

Are you familiar with the sigmoid curve? It’s a mathematical concept resembling an “S” shape when graphed, and it’s a powerful metaphor:

“It is the line of all things human, of our own lives, of organisations and businesses, of governments, empires, and alliances, of democracy itself and its many and varied institutions.” — Charles Handy, The Second Curve

The sigmoid curve can be used to model growth patterns in various fields ranging from biology and economics to technology and learning. The “S” represents a gradual increase, followed by a period of rapid growth, and then a tapering off into a plateau before eventual decline.

The decline part sounds a bit depressing, but it doesn’t have to be. As social philosopher Charles Handy points out, there can always be a second curve:

The challenge, as you can see from the illustration, is that the second curve needs to start before the first one peaks. How are you supposed to know when the peak is coming?

The textbook examples of failing to foresee the peak in business are Kodak and Blockbuster, two highly successful companies that ignored the impact of digital technology until it was too late. (Kodak lost out to the smartphone/digital cameras, and Blockbuster lost out to Netflix.) I wonder how many organisations will do the same with AI.

While it can be hard to embrace change when things are going well, it’s even harder to do so when things are going badly. This is as true for individuals as it is for organisations. We are more likely to lack the time, energy, and/or resources to pursue alternatives.

I started thinking about second curves a couple of weeks ago after a friend remarked on my career. They thought that I had taken some bold shifts at the right time. I explained that, while luck has certainly played a role, I’ve always chosen to leave a job just before hitting my peak—when the energy and growth opportunities were still there.

Here’s an example. One of the reasons I left my first job at a renowned digital agency was because I believed the agency business model was misaligned with the future of software development, and software was already eating the world. The other reason was feeling a bit too comfortable. (Ironically, I’d never forgotten what the agency’s co-founder James Hilton had said when announcing his departure after nearly 20 years at the company: “If you’re not shitting yourself, you’re not doing something new.”) So when the opportunity came to join an early-stage tech venture, I took it, even though there were plenty of agency roles still to climb and interesting challenges to tackle.

I hadn’t thought much about second-curve thinking since reading Charles Handy’s The Second Curve in 2015. It clearly made more of an impression than I’d realised. Flicking back through the pages almost ten years on, I spotted some satisfying parallels:

“André Previn, the classical musician, had great success in Hollywood as a young man, composing film scores, but gave it all up to come to Britain and concentrate on performing and conducting. He explained that he woke up one morning with no pain in his stomach at the thought of what he had to do that day. At that point, he knew it was time to leave.”

Hilton’s exact sentiment, minus the swearing!

The freedom to act on second-curve thinking is a privilege, no doubt about it. But maybe that’s exactly why everyone who can pursue it should. We can’t create a better, fairer world without learning to embrace renewal and change. Which is exactly what second-curve thinking promotes.

Thanks so much for reading,

Lauren